Today marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Despite what is usually said about the 19th Amendment, it only prohibited states from using sex as disqualifying criteria for voting rights – it didn’t “grant” women the positive right to vote per se. Far from an inconsequential detail, this is a critical distinction that yields much more clarity in regard to federalism, constitutional intent, and the history of women’s suffrage in the United States than the typical narrative does.

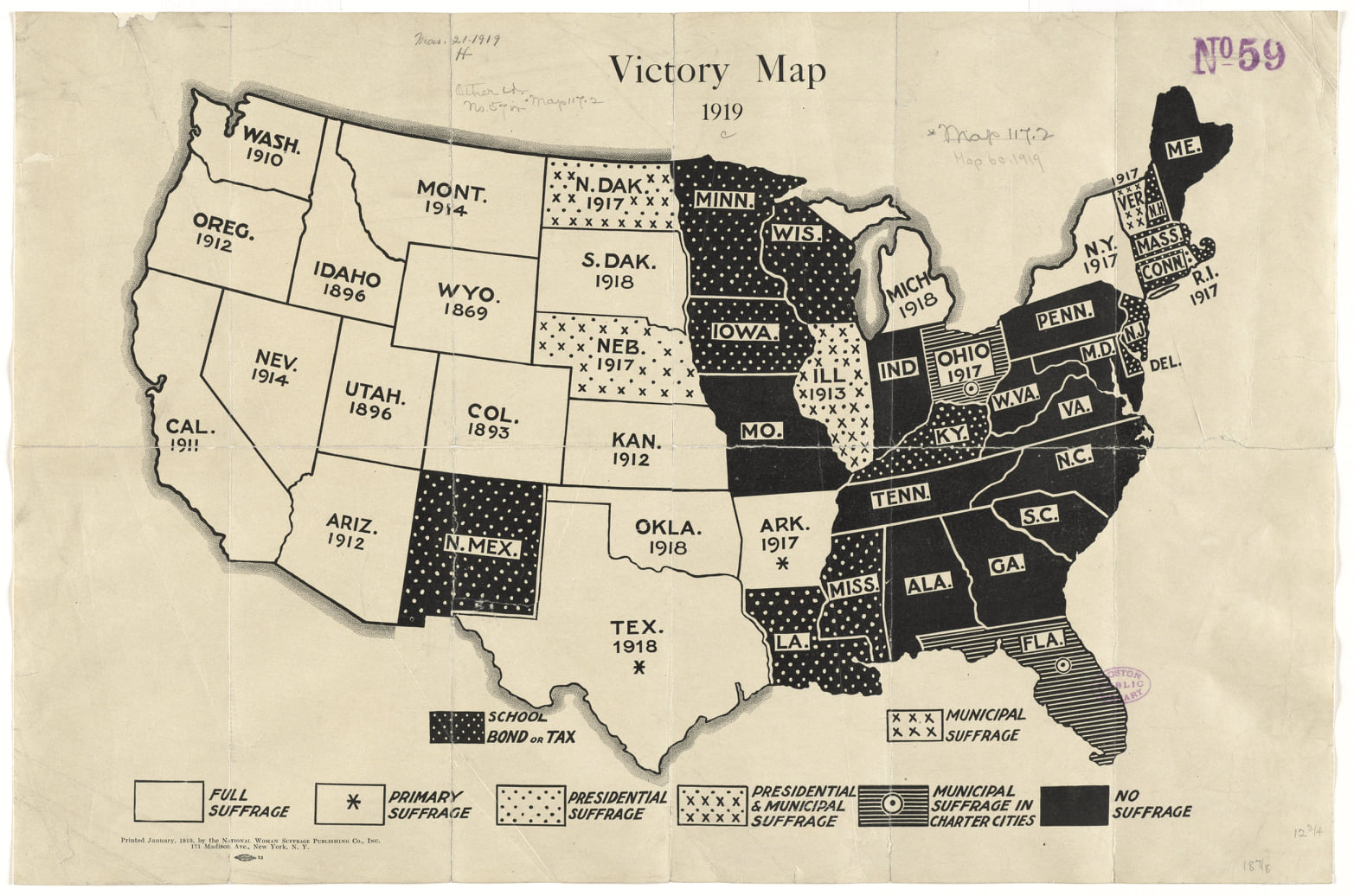

Long prior to 1920, many states recognized the right to vote for women, with many extending full suffrage (See the graphic below for that shows the full picture of this in 1919).

Even during the founding period, women voted in some circumstances. For instance, in New Jersey, women had full enfranchisement until 1807, when its state constitution was altered to prohibit it. For New Hampshire likewise, the state’s 1776 constitution did not prohibit women from voting and they did so into the 1780s.

After that era, states did impose restrictions to disqualify many individuals from voting – usually on the basis of property ownership thresholds but also on the basis of sex – but many regions lifted the sex-based criteria long before 1920. As such, the 19th Amendment was more of a limitation mechanism against the states than it was a positive instrument for women’s rights, and many women voted long before its ratification in 1920.

I can’t help but think that the common inversion of these truths has largely been an undertaking designed to portray the federal government as a benevolent grantor of rights, and a corrector of women’s oppression when the historical reality was truly much more nuanced than that.

On the contrary, it was the states – under the doctrine of federalism and state’s rights – that enfranchised women and eventually ratified the 19th Amendment.

- Today in History: Newly Independent American States Sign Treaty of Alliance With France - February 6, 2024

- Thomas Paine: A Lifetime of Radicalism - October 3, 2023

- Thomas Paine Played Dodgeball With Death - September 23, 2023